A relatively high rate of unemployment across the nation, coupled with a freeze on immigration, and consequently population growth, might ordinarily spell bad news for the housing market. Instead, Australian capital city average dwelling prices rose 0.2% in October, according to CoreLogic, the first monthly gain since April and hot on the heels of a cumulative contraction of almost 3% between April and September.

Prices are being held up by a combination of low interest rates, regulatory easing and government support. However, we would have expected at this point in the crisis for downside pressures to be more dominant than they have been, and a number of risks remain for investors seeking to increase their exposure to residential property.

The true state of play really depends on your location. For example, risks are higher in cities such as Sydney and Melbourne, which are more reliant on migrant intake but lower in other markets which aren't so exposed to immigration nor dependent upon proximity to high density CBDs.

Likewise, within markets, inner suburban apartments are more at risk than outer suburban houses given the shift away from inner cities.

Melbourne prices, in particular, fell again in October by 0.2%, now down 5.6% from their March high. Melbourne has obviously been impacted by the broader hit to its economy from the second round of lockdowns. Sydney has been far less affected by the second wave of the pandemic; but while house prices in the Harbour City rose by 0.1% in October, they nonetheless fell significantly -2.9% - from April to September.

Other capital cities performed more strongly, with Adelaide and Brisbane finally picking up after years of underperformance compared to Sydney and Melbourne; Canberra is benefitting from strength in public sector employment; and Perth and Darwin are starting to recover after multi-year bear markets helped by the recovery in mining.

Regional prices rose by 0.9%, in part reflecting lower levels of indebtedness in those areas as well as less reliance on immigration and a more attractive environment for workers looking to move away from cities for lifestyle reasons.

Meanwhile unit prices actually fell by 0.2%, possibly reflecting the change in the lifestyle preference towards houses rather than apartments as more people work from home; and the weakness in rental markets as a result of the drop in overseas migration.

Longer-term risks to the upswing

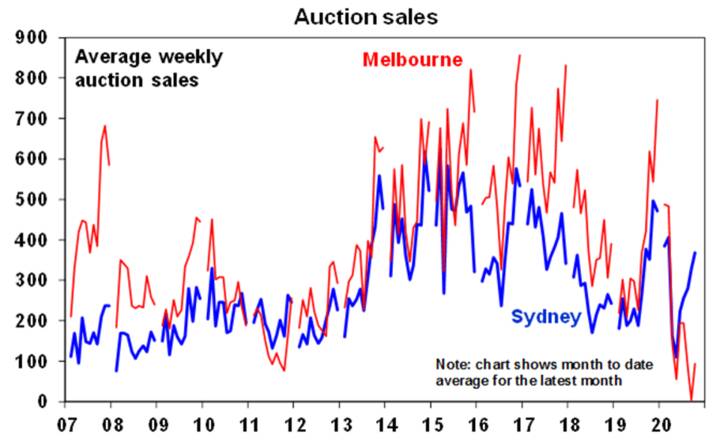

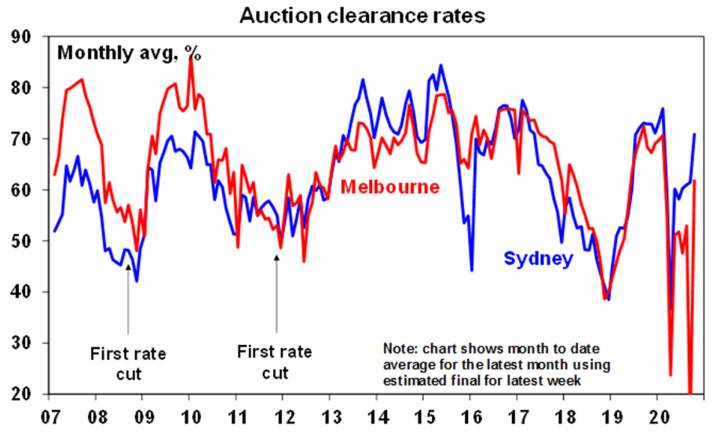

The underlying data supports a narrative where positive tailwinds continue to overcome downside risk in residential property, with Sydney seeing similar levels of sales activity and clearances at this time last year and Melbourne picking up quickly after reopening from the second set of lockdowns.

Source: CoreLogic

Source: CoreLogic

After a slow couple of months, there appears to be a lot of pent up demand in local markets. Throughout the pandemic even when prices were low, sellers were scarce, and now on reopening there are a number of concurrent forces driving a quick uptick in residential property prices, including government incentives such as: stamp duty concessions and the expansion of the First Home Loan Deposit Scheme; the removal of responsible lending obligations early next year; ongoing bank high payment holidays; and government income support measures. In a season where rates are low and many are looking for a change of lifestyle, it’s a heady mix of stimulus to buy that could rapidly lead to another round of Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), especially in Sydney and Melbourne.

There are a lot of reasons, however, for investors to be more cautious over a longer horizon. A number of these support measures are artificial and will eventually be phased out along with broader economic measures, such as JobKeeper and the increases to JobSeeker. There is no guarantee that this wind down will be accompanied by falling unemployment. Furthermore, it's also hard to see in the longer term how the reversal in net immigration from around 240,000 people per annum to an expected net outflow of people won’t have a significant impact.

Immigration contributed significantly to the population growth that has fuelled the Australian housing market over the past 15 years as the market became chronically undersupplied. The collapse of this dynamic is likely over the coming years to drive a sharp reduction in demand for housing, relative to supply, which would eventually be reflected in house prices.

There is a high risk that despite a short-term uptick these twin negative forces could reassert themselves on the market, especially in Melbourne and inner Sydney, given already falling rents and high vacancy rates in these areas as well as the trend running against them as more residents work from home.

However, outer suburban areas and houses in these cities are likely to continue to be more resilient to these headwinds, reflecting the new normal where a lower premium is placed on proximity, a trend likely to also be replicated in other capitals and regional markets.